Let Your Microcontroller Talk

Learn how to enable a microcontroller’s USB interface and exchange data with a host Linux machine. We’ll first emulate a serial port, then build a pen-drive-type device, and finally create a fully custom data transfer interface.

Many microcontrollers live their lives in isolation: Embedded in your toaster, washing machine or other utility device, they communicate only with the sensors that give them information and the actuators that let them control things. Another class of microcontroller communicates with peer devices via buses such as the CAN bus (particularly in cars) or MOD bus in an industrial environment. In this way, a group of devices can cooperate to provide a distributed functionality: In the case of modules on the CAN bus in a car, one might look after the buttons on the steering wheel, whilst another will accept commands to activate a turn signal or open the sunroof. Communication between the modules is the key here.

Larger, more powerful devices might have an Ethernet or WiFi port for communication with a remote server or for configuration. The devices I will discuss today have a USB interface that allows configuration, uploading or downloading data (such as music in a simple, portable music player), or software updates. USB was the natural successor to the once ubiquitous RS-232 serial interface. RS-232 was not well-defined, with many variants in the protocol and the hardware implementation. Its early use was in communicating between computers and modems (sometimes via acoustic couplers), and computers and “dumb” terminals.

USB was designed to fix some of those issues, as well as to increase bandwidth and general flexibility. Unlike RS-232, USB is more than a point-to-point link. Multiple devices can be supported by a single host via hubs. USB is also more or less plug-and-play for the majority of USB setups, such as serial port emulation, block devices (e.g., mass storage such as thumb drives and SD card adapters), and audio devices such as microphones and speakers. Devices whose requirements don’t fall into those categories can implement their own transfer protocols using the “bulk transfer” class.

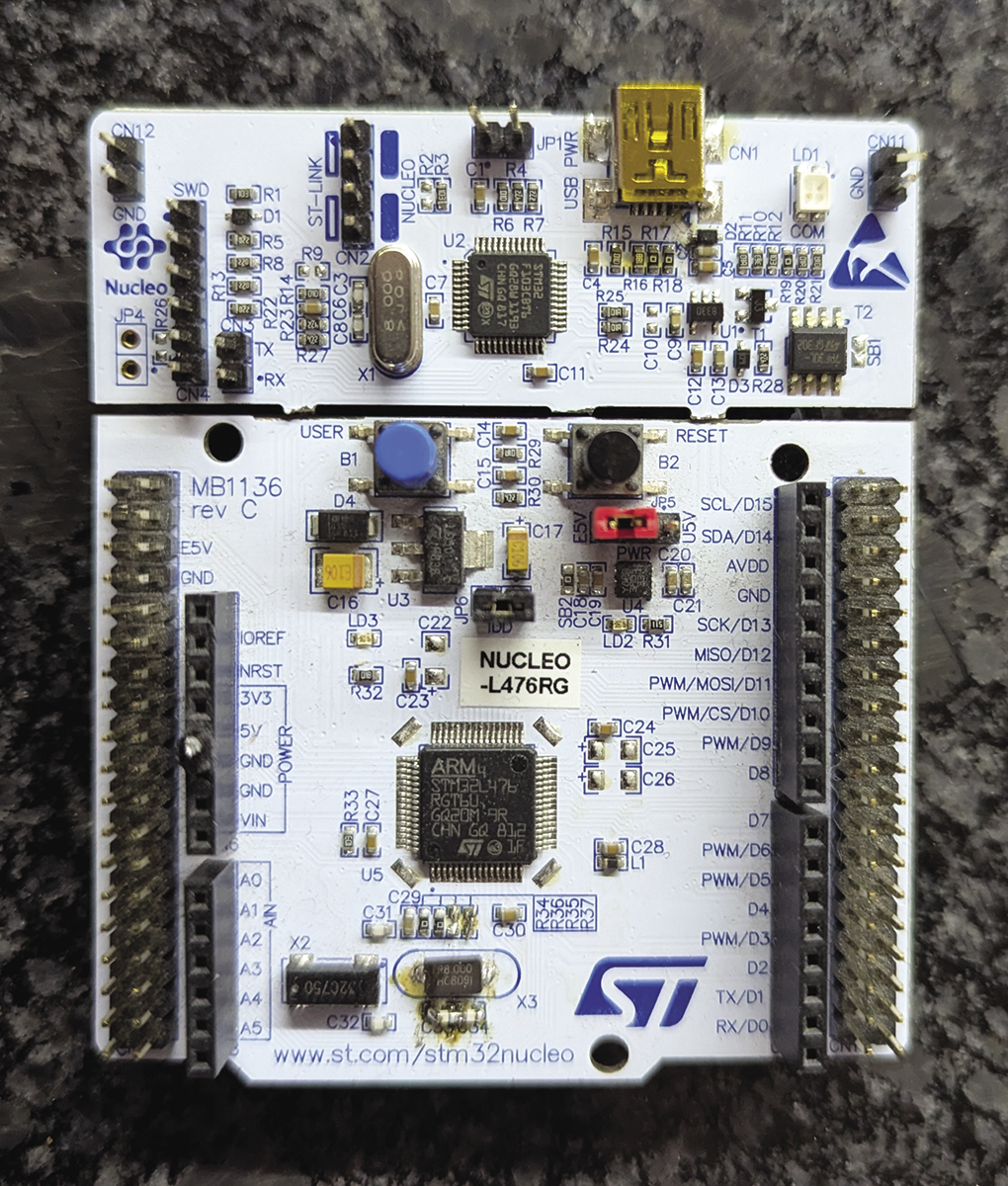

I will demonstrate how to set up a popular family of microcontrollers to implement serial port emulation or to be a mass storage device that will appear as a Linux block device that can be formatted, read, and written. Finally, I’ll demonstrate a custom protocol using bulk transfers that lets you communicate with an application using the excellent libusb library, which allows user-mode programs to talk to a USB device without a device driver. I will be using an STMicroelectronics development board for these examples (specifically the NUCLEO-L476RG, Figure 1), together with their excellent IDE, STM32CubeIDE. However, my main focus is on how USB enables communicating with a host computer, so the general principles are equally applicable to other microcontroller families.

Serial Port Emulation and the CDC Class

Emulating a serial port is the simplest way to let a microcontroller and the host communicate over USB. Most operating systems will recognize a serial port emulation of the Communication Device Class (CDC), and Linux in particular will assign the name /dev/ttyACM0 to the first CDC device. You may have to adjust permissions to avoid using root to access this device, and that may be done through custom udev rules. Once connected, you can use any terminal program such as minicom to exchange data with your microcontroller.

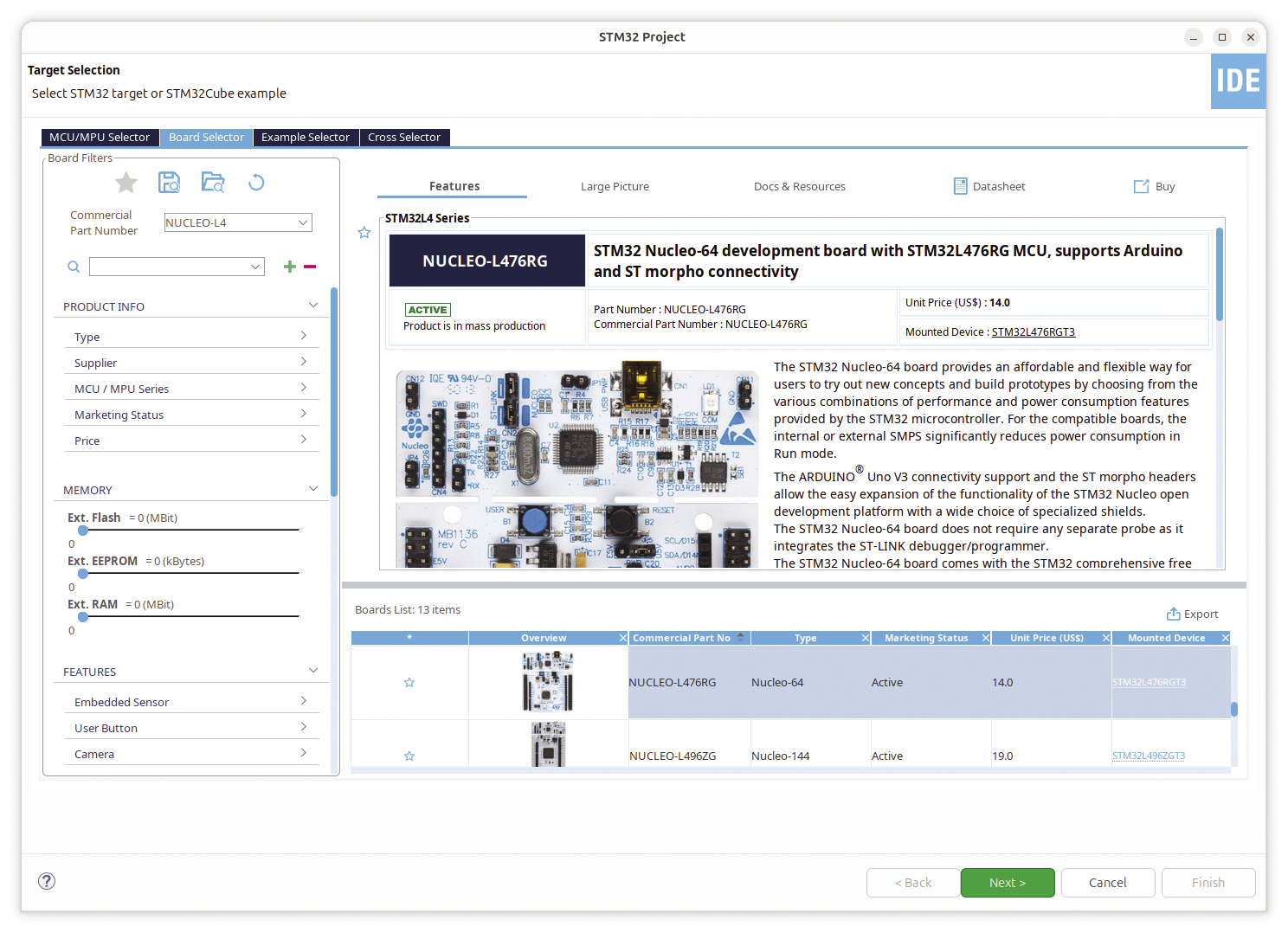

If you’re using STM32CubeIDE for the first time, see the “Set Up STM32CubeIDE” box for some required initial steps, such as creating an account and adding login credentials to the application. Start a new project in STM32CubeIDE (File | New | STM32 Project) and use the Board Selector to find and select your development board (Figure 2).

When you download the STM32CubeIDE software package from the STMicroelectronics website, make sure to get the latest 1.x version (which was 1.19.0 at the time of writing), not the new version 2.0, as it can no longer generate

*.ioc files that let you graphically configure your project. (The functionality is now part of a separate STM32CubeMX package that’s also available for Linux, but those two are no longer integrated.) Accessing the download files requires setting up an account on the st.com site, and you need to provide a working email address as it needs to be verified.For Debian- or RPM-based distributions you can download a Zip file that contains a shell script that (after unpacking and launching with

sudo) will in turn unpack and install some .deb or .rpm packages. Alternatively, you can download a generic installer for Linux, again as a Zip file (st-stm32cubeide_1.19.0_25607_20250703_0907_amd64.deb_bundle.sh.zip). Unpack that Zip file, which also contains an installer script. The installer script expects you to provide a target directory. If you run it without an option, it will attempt to install to a temporary folder and then complain about it and abort. To put all files into /opt/stm32, runsudo ./st-stm32cubeide_1.19.0_25607_20250703_0907_amd64.sh /opt/stm32When the installation is complete and you’re running the program for the first time, click Help | STM32Cube updates | Connection to myST and enter your login credentials. You can then proceed with your first project. (by Hans-Georg Eßer)

You'll use USB connections to connect your development board. One is the programming port (the dev board has a separate microcontroller that communicates with the IDE to manage programming and debugging on your target), and the second is to the USB port on the dev board. If your dev board does not have a USB connector but your microcontroller supports USB, you’ll have to refer to the manual, find the two USB pins, and connect a USB cable (D+ and D-) to those pins.

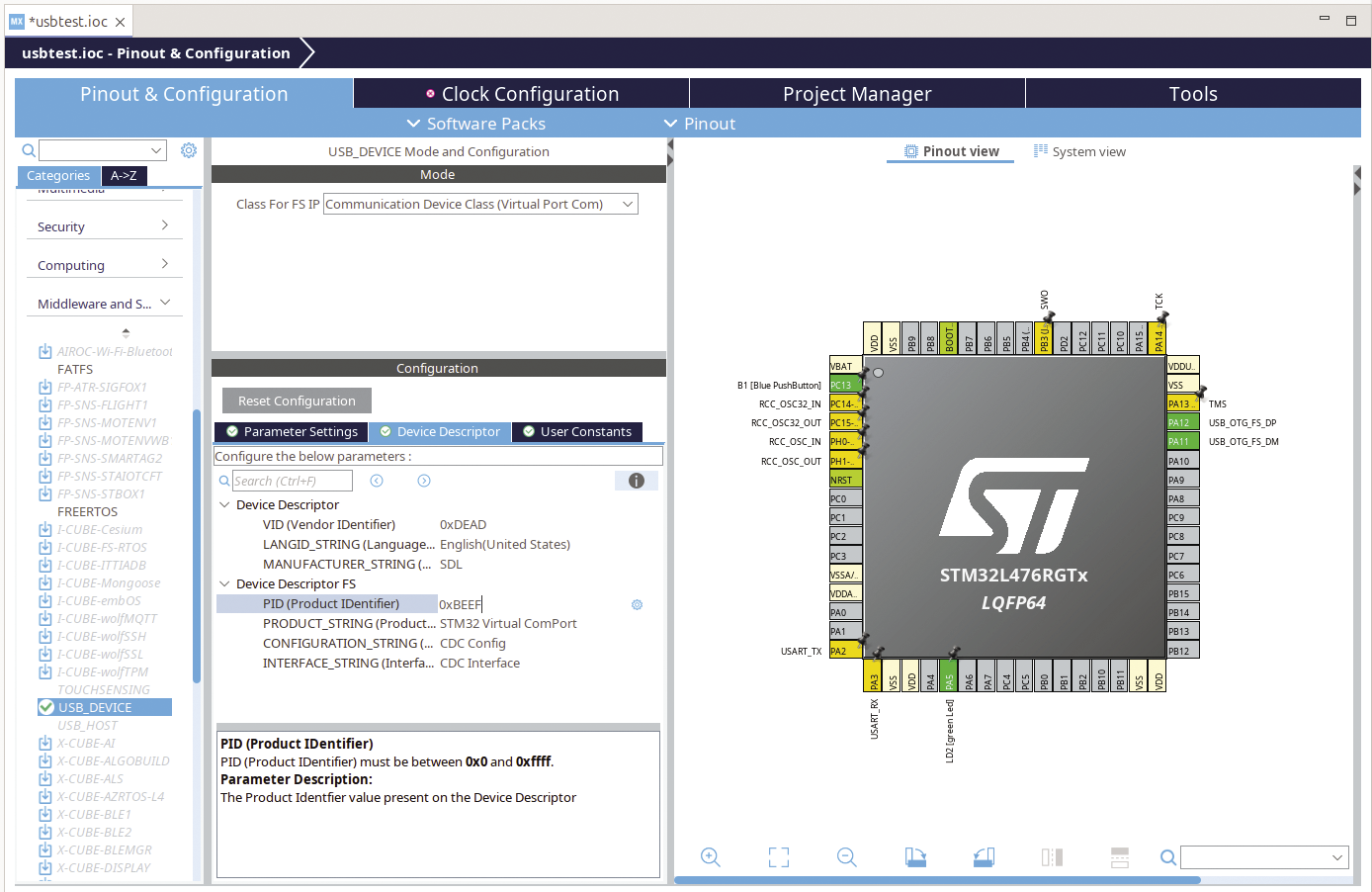

In the IDE, set up the microcontroller’s clock configuration as appropriate to your board, making sure there is a clock source for USB, which is typically 48MHz. Next, go to Connectivity on the Pinout and Configuration tab and enable USB_OTG_FS (which may have a slightly different name depending of your microcontroller). In the Mode window, select device only. Back on the Pinout and Configuration tab, scroll down to Middleware and Software Packs and select USB_DEVICE. This will pull in the driver support code, which requires some configuration.

First select the class, in this case Communication Device Class (Virtual Port Com). Below, change the VID (vendor ID) and PID (product ID) to numbers of your choice (Figure 3). These numbers are assigned by the USB Implementers Forum for commercial devices, but for our purposes we can use what we please. I like to use hexadecimal numbers such as 0xFEED, 0xC0DE, simply because they stand out in the lsusb output. You may also need these numbers when you come to write udev rules that change permissions. You can also change the PRODUCT_STRING and MANUFACTURER_STRING constants directly below VID and PID, but this is optional: They show up in lsusb, but don’t affect device operation.

With that, you’re done. If you build the project and then run it, you should see something like this in lsusb:

$ lsusb -d dead:beef

Bus 001 Device 087: ID dead:beef SDL STM32 Virtual ComPort

Here dead and beef are my chosen VID and PID, and I have modified the product string to SDL. In the device tree, you should see an entry for the new device:

$ ls /dev/ttyACM*

/dev/ttyACM0Adding the Firmware

That’s all well and good, but you need to add some code in order to use the virtual serial port. For example, you could attempt to use printf to output data to a host terminal. This is fairly straightforward:

- The file

USB_DEVICE/App/usbd_cdc_if.c, has an area where you can add private code. It won’t be overwritten when you regenerate the code. Add the functionusb_write_chars(Listing 1, lines 1-3). - Then, in

Core/Src/main.c, locate thePrivate typedefarea and add an external definition of this method (Listing 1, line 7) between the/* USER CODE BEGIN PTD */and/* USER CODE END PTD */comments. - Further down in

main.cin thePrivate user codesection, add the_writefunction (lines 10-15) between the/* USER CODE BEGIN 0 */and/* USER CODE END 0 */comments. - You will need to also include

"sys/unistd.h"for the definition ofSTDOUT_FILENO. - Finally, modify the

whileloop in themainfunction’sInfinite looparea so that it looks like lines 18-25 of Listing 1.

Listing 1: Code Snippets

01 // in usbd_cdc_if.c

02 void usb_write_chars(uint8_t *buffer, uint8_t length) {

03 while(CDC_Transmit_FS(buffer, length));

04 }

05

06 // in main.c, "Private typedef" area

07 void usb_write_chars(uint8_t *buffer, uint8_t length);

08

09 // in main.c, "Private user code" area

10 int _write(int file, char *ptr, int len) {

11 if(file == STDOUT_FILENO) {

12 usb_write_chars( (uint8_t *)ptr, len);

13 }

14 return len;

15 }

16

17 // in main.c, "Infinite loop" area

18 while (1)

19 {

20 /* USER CODE END WHILE */

21

22 /* USER CODE BEGIN 3 */

23 printf("hello\n");

24 HAL_Delay(2000);

25 }After you compile and run the modified code and then run the shell command

minicom --device /dev/ttyACM0you should see “hello” printed every two seconds. As an aside, the baud rate you normally have to set for serial port connections is irrelevant here. Receiving data from the host is only a little more complicated. For brevity, I’ve omitted it here. You can find the code for this project in my serial port GitHub repository.

Mass Storage Class

The USB mass storage class is used for pen drives and other devices that can support a filesystem. All the firmware has to do is to tell the host how many blocks of storage (typically flash memory) it has, so that the host knows the capacity, and then read or write those blocks on command.

As before, begin by starting a new project, set up the clock configuration and USB_OTG_FS in the Connectivity pane. Then scroll to the Middleware and Software Packs section and select USB_DEVICE. In the class selection area, pick Mass Storage Class (which is different from the first example). Again, choose a VID and PID and change the strings if desired. Switch to the Parameter Settings tab and set MSC_MEDIA_PACKET (Media I/O buffer Size) to 2048. In this example code, you will use a portion of the microcontroller’s internal program flash as storage, so it is important that the block size matches the block size of the flash. (The block size is he smallest unit of flash that can be erased and rewritten.) This block size is reported to the host during USB enumeration.

If your development board has an external flash chip mounted, you can use that as the storage medium. Using a chunk of the microcontroller’s program flash as storage requires a little linker magic to reserve the upper portion of flash and provide a pointer _mass_storage_data to it. Then you can use the HAL functions to write to it; reading is simply a matter of accessing it via the pointer you’ve provided. In the linker script STM32L476RGTX_FLASH.ld (available online), modify lines 36-63 using the code in Listing 2.

Listing 2: Modified Code for STM32L476RGTX_FLASH.ld (Excerpt)

/* Entry Point */

ENTRY(Reset_Handler)

/* Highest address of the user mode stack */

_estack = ORIGIN(RAM) + LENGTH(RAM); /* end of "RAM" Ram type memory */

_mass_storage_data = ORIGIN(MASS_STORAGE_DATA);

_Min_Heap_Size = 0x200; /* required amount of heap */

_Min_Stack_Size = 0x400; /* required amount of stack */

/* Memories definition */

MEMORY

{

RAM (xrw) : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 96K

RAM2 (xrw) : ORIGIN = 0x10000000, LENGTH = 32K

FLASH (rx) : ORIGIN = 0x8000000, LENGTH = 512K

MASS_STORAGE_DATA (rw) : ORIGIN = 0x8080000, LENGTH = 512K

}

/* Sections */

SECTIONS

{

._mass_storage_data :

{

KEEP(*(._mass_storage_data))

} >MASS_STORAGE_DATA

In Listing 2, _mass_storage_data points to the reserved chunk of flash, which in this case is the upper 512KB of the microcontroller’s 1MB flash. All the further code you need to add resides in USB_DEVICE/App/usbd_storage_if.c. This file is generated by the IDE, and any code you add must be between the guard comments (from /* USER CODE BEGIN xxx */ to /* USER CODE END xxx */), so that it will not be overwritten by the IDE.

For example, in order to reference the reserved flash storage, you need to add the line

extern uint8_t _mass_storage_data [NUM_BLOCKS*BLOCK_SIZE];

between the /* USER CODE BEGIN EXPORTED_VARIABLES */ and /* USER CODE END EXPORTED_VARIABLES */ comments. Next, two defines are required to set up the storage media, which should be placed between /* USER CODE BEGIN PRIVATE_DEFINES */ and /* USER CODE END PRIVATE_DEFINES */:

#define NUM_BLOCKS 1024*512/MSC_MEDIA_PACKET

#define BLOCK_SIZE MSC_MEDIA_PACKETHere, MSC_MEDIA_PACKET is the constant that you configured earlier in the GUI-based device setup, and this number will be sent to the host computer so it knows the block size.

Reading and Writing the Flash

Now you must add code to three important functions: STORAGE_GetCapacity_FS, STORAGE_Read_FS, and STORAGE_Write_FS. With STORAGE_GetCapacity_FS, you’re informing the host of your capacity (Listing 3, lines 1-7); reading is as simple as copying data from the requested block to the provided buffer with memcpy (lines 9-14). Writing, however, is a little more complex (lines 16-54): First you must unlock the flash and erase the block requested, which is a characteristic of flash memory. Only 0s may be programmed, so erasing the block sets all bits to 1s. The microcontroller’s internal flash may only be written in words of 64-bit length, so you write the whole block in a loop. Finally you re-lock the flash, and we are done.

Listing 3: Storage Functions in usbd_storage_if.c

01 int8_t STORAGE_GetCapacity_FS(uint8_t lun, uint32_t *block_num, uint16_t *block_size) {

02 /* USER CODE BEGIN 3 */

03 *block_num = NUM_BLOCKS;

04 *block_size = BLOCK_SIZE;

05 return (USBD_OK);

06 /* USER CODE END 3 */

07 }

08

09 int8_t STORAGE_Read_FS(uint8_t lun, uint8_t *buf, uint32_t blk_addr, uint16_t blk_len) {

10 /* USER CODE BEGIN 6 */

11 memcpy(buf, &_mass_storage_data[blk_addr * BLOCK_SIZE], blk_len * BLOCK_SIZE);

12 return (USBD_OK);

13 /* USER CODE END 6 */

14 }

15

16 int8_t STORAGE_Write_FS(uint8_t lun, uint8_t *buf, uint32_t blk_addr, uint16_t blk_len) {

17 /* USER CODE BEGIN 7 */

18 FLASH_EraseInitTypeDef eraseInit;

19 HAL_StatusTypeDef res;

20

21 eraseInit.TypeErase = FLASH_TYPEERASE_PAGES;

22 eraseInit.Banks = FLASH_BANK_2;

23 eraseInit.NbPages = 1;

24 eraseInit.Page = blk_addr;

25

26 HAL_FLASH_Unlock();

27

28 uint32_t pageError;

29 res = HAL_FLASHEx_Erase(&eraseInit, &pageError);

30

31 if (res != HAL_OK) {

32 fprintf(stderr, "FLASH erase error %d\n", res);

33 HAL_FLASH_Lock();

34 return USBD_FAIL;

35 }

36

37 uint64_t *ptr = (uint64_t *)buf;

38 uint32_t addr = (uint32_t) (uint32_t)&_mass_storage_data[0] + blk_addr * BLOCK_SIZE;

39

40 for(int i=0; i < BLOCK_SIZE; i += sizeof(uint64_t), addr+=sizeof(uint64_t)) {

41 res = HAL_FLASH_Program(FLASH_TYPEPROGRAM_DOUBLEWORD, addr, *ptr++);

42

43 if(res != HAL_OK) {

44 fprintf(stderr, "FLASH write error %lx\n", HAL_FLASH_GetError());

45 HAL_FLASH_Lock();

46 return USBD_FAIL;

47 }

48 }

49

50 HAL_FLASH_Lock();

51

52 return (USBD_OK);

53 /* USER CODE END 7 */

54 }Connecting to Your Computer

If you connect your board to the computer and run lsusb, your device should appear with the device descriptor you set up earlier. In my case the output looks like this:

Bus 001 Device 120: ID cafe:babe SDL STM32 Mass Storage

More interestingly, it should also appear as a block device in the output of the lsblk command. In my case (Listing 4), the second entry shows a 512KB disk. From here, you can go ahead and create a filesystem and copy files to and from it just like any flash disk. Writing is somewhat slow due to the way writes are performed: If you were to use an external flash memory with full block write capabilities, it would be faster. So be patient when formatting etc. – it hasn’t crashed; it’s just a bit slow! It’s also worth noting that gparted gets confused by such a small disk that, to be fair, is actually smaller that the USB specification allows for. It does work but complains a bit. fdisk, on the other hand, takes it in its stride.

Listing 4: Running lsblk

$ lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sda 8:0 1 0B 0 disk

sdb 8:16 1 512K 0 disk

nvme0n1 259:0 0 1.8T 0 disk /home

nvme1n1 259:1 0 238.5G 0 disk

`‑nvme1n1p1 259:2 0 94M 0 part /boot/efi

`‑nvme1n1p2 259:3 0 4.6G 0 part [SWAP]

`‑nvme1n1p3 259:4 0 233.8G 0 part /Partitioning, Formatting and Testing

The Red Hat blog provides instructions for using fdisk. You can pretty much follow the defaults after opening the device with sudo fdisk /dev/sdb, creating a new partition (n) that’s a primary partition with partition number 1 that spans all sectors of the device and writing the modified partition table to disk (w). Once you do this, you should then see a new partition in the lsblk output:

$ lsblk /dev/sdb

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sdb 8:16 1 512K 0 disk

`-sdb1 8:17 1 510K 0 partAfter making a filesystem and mounting it with

sudo mkfs.fat /dev/sdb1

sudo mkdir -p /mnt/usb_disk

sudo mount -t vfat /dev/sdb1 /mnt/usb_diskyou can copy files to and from the disk. Of course, this is not an ideal use case for communication between a host and your USB application. Unless your application understands the format of the data stored in flash (in this case it’s a FAT file system), then your local application cannot readily make use of it. So this class is typically used for such things as thumb drives. I have seen devices that support multiple virtual devices, with an instance of the mass storage class being used to provide documentation about the gadget that you can access when you plug it in. You can download the full code from my mass storage GitHub repo [6].

Bulk Transfer Class

This is the most interesting class in my view as it enables high-speed data transfer in binary with any data structure you require. But this flexibility comes at a price. STM32CubeIDE does not support this class directly, so you first generate code for a human interface device (HID) class (that’s the class for keyboards, mice, etc.), and then you hijack some of the code and replace the device descriptors with those of the bulk transfer class. On the host side, you need to write your own software to handle the interface, but with the help of the very capable open-source libusb, the framework for this is just a few lines of code.

To get started, open a new project, and as before set up the clock configuration and the USB device. In the Middleware and Software Packs select USB_DEVICE, and for the class, select Custom Human Interface Device Class (HID). To make this into a bulk transfer device, you need to add custom descriptors. So add an include file usbd_vendor.h to your include directory and an implementation file usbd_vendor.c to the source code directory – you can find those two files in my bulk transfer GitHub repo, located in the Drivers/USBD_Vendor/Inc/ and Drivers/USBD_Vendor/Src/ folders. One of the implemented functions in usbd_vendor.c is USBD_Vendor_Send, and that will be used in main.c.

In Core/Src/main.c, you need to include the header file with

#include "usbd_vendor.h"in the Includes user code section. In the Infinite loop section at the end of the main function, add this:

uint8_t buffer[VENDOR_EP_SIZE];

USBD_Vendor_Send(buffer, VENDOR_EP_SIZE);inside the otherwise empty while loop. That will continuously send 64-byte packets to the host.

Connecting to Your Computer

As before, lsusb should show the device:

$ lsusb -d dead:beef

Bus 001 Device 070: ID dead:beef SDL Bulk transfer

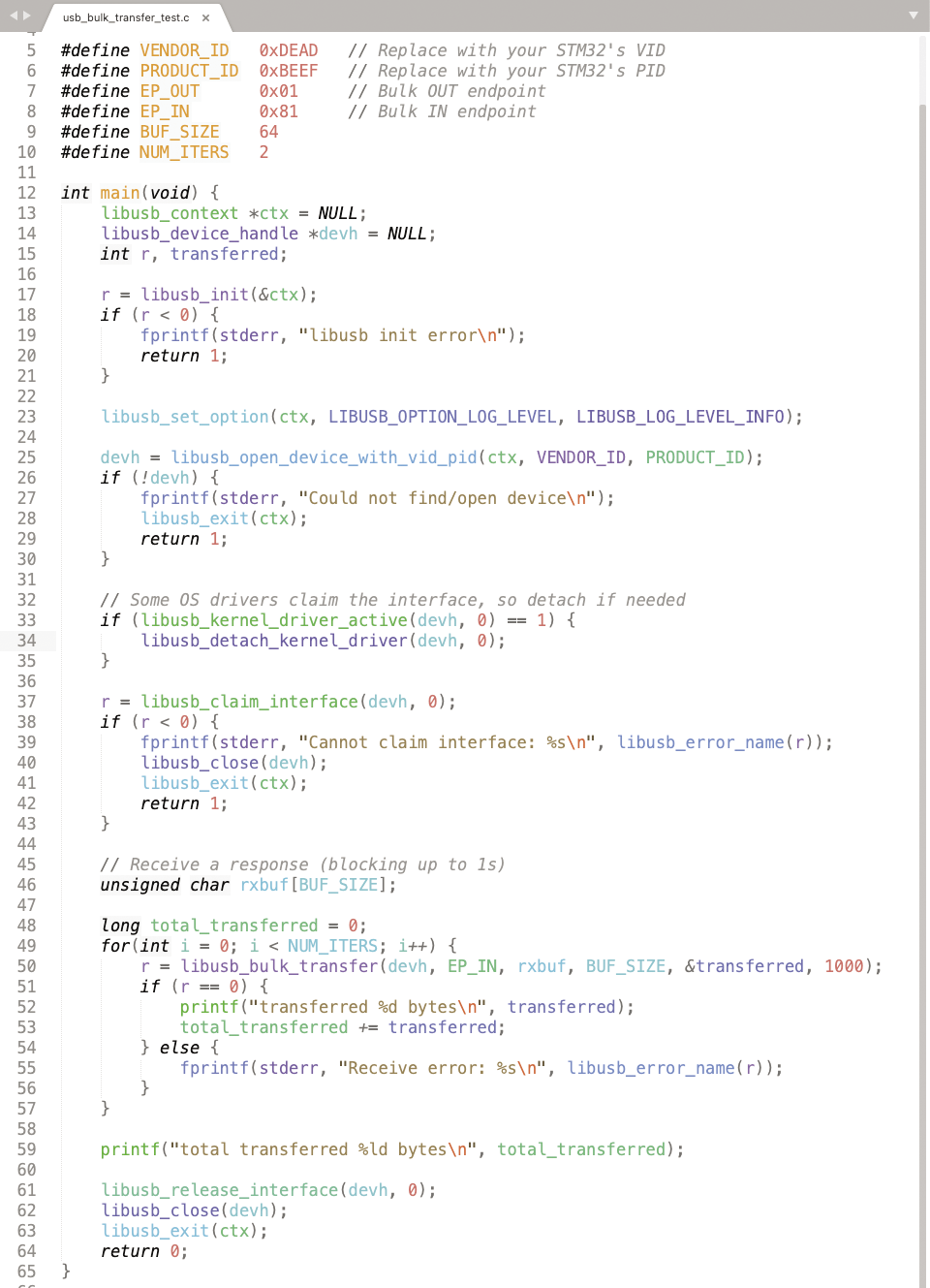

and the verbosity option -v will show the bulk transfer in and out endpoints. In order to receive the data which the device is sending, we need a simple host program that connects to the device with the aid of libusb; Figure 4 shows the contents of usb_bulk_transfer_test.c. You can compile it with

cc usb_bulk_transfer_test.c -o usb_bulk_transfer_test $(pkg-config --cflags --libs libusb-1.0) -lm(after installing libusb and possibly pkg-config; on a Ubuntu machine with some development tools already installed

sudo apt install libusb-1.0-0-dev pkg-config

did the trick).

libusb to talk to the bulk transfer device.Wrap Up

I’ve presented three possible ways to connect a microcontroller to a host machine. The serial emulation is particularly useful if you want to add a console to your firmware, where you can type commands to perform operations and query data.

For streaming data, the bulk transfer class is the most useful: You can superimpose any format on the data that you require. One method I find very useful is to define a data structure or record, literally a C struct, that both the device and the host know about. Then the sender can populate this structure’s members and send it to the recipient, which then casts the received raw data array into the same struct and finally extracts the data.

The mass storage class certainly has its uses, too, but it is really designed for implementing pen drives and the like. It comes into its own when your device supports multiple USB interfaces: It can then serve as a useful way to provide documentation, source code, etc. that’s bundled with your firmware.

If you’re interested in more detailed descriptions of the IDE, you can have a look at the “Introduction to STM32CubeIDE” article on STMicroelectronics’ Wiki. The page also links to several hours of video tutorials, all hosted on YouTube.