Hands Free

Have you found yourself following instructions on a device for repairing equipment or been half-way through a recipe, up to your elbows in grime or ingredients, then needed to turn or scroll down a page? Wouldn’t you rather your Raspberry Pi do the honors?

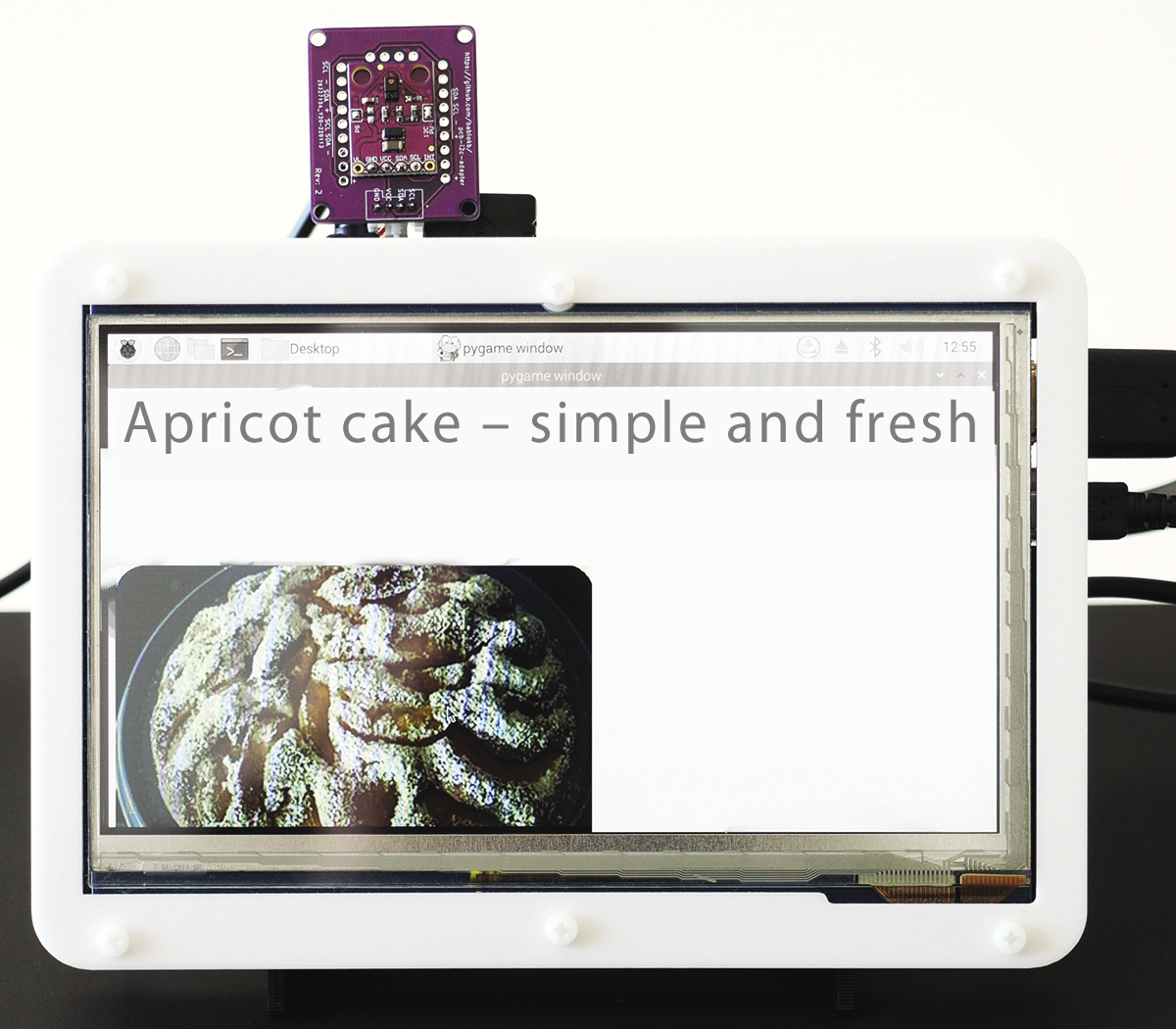

This article is about the joy of tinkering, and the project I look at is suitable for all kinds of situations when your hands are full or just dirty. The hardware requirements turn out to be quite low: a Raspberry Pi, a screen, and a gesture sensor. My choice of sensor was the APDS9960 (Figure 1), for which you can get breakouts and an I2C connector for a low price at the usual dealers ($3.20-$7.50). However, you should note whether the sensor has soldered jumpers. The left jumper (PS) controls the power supply of the infrared lamp with the pin for positive supply voltage (VCC) and definitely needs to be closed. The right jumper (labelled 12C PU on the sensor in Figure 1) enables the pullups on the clock line (SCL) and the data line (SDA), which is superfluous on the Raspberry Pi; however, it doesn’t hurt to have it.

Modern kitchens sometimes feature permanently installed screens. If you don’t have one, go for a medium-sized TFT screen like the 7-inch Pi screen or a model by Waveshare (Figure 2). If you are currently facing the problem that the Raspberry Pi is difficult to get, as many people have, you can go for a laptop instead, which I talk about later in this article.

Installing the Software

The Pi Image Viewer program is implemented in Python and is very minimalist. In fact, it is an image viewer that performs precisely one function: scrolling through an image in response to gestures. The software would even work with a small four-inch screen with a Raspberry Pi clamped behind it, but it would not be particularly user friendly.

You can pick up the software for a gesture-driven recipe book on GitHub by cloning the repository and installing the software with the commands

git clone https://github.com/bablokb/pi-image-viewer.git

cd pi-image-viewer

sudo tools/install

Additional information is provided in the installation instructions in the Readme.md file.

Implementation

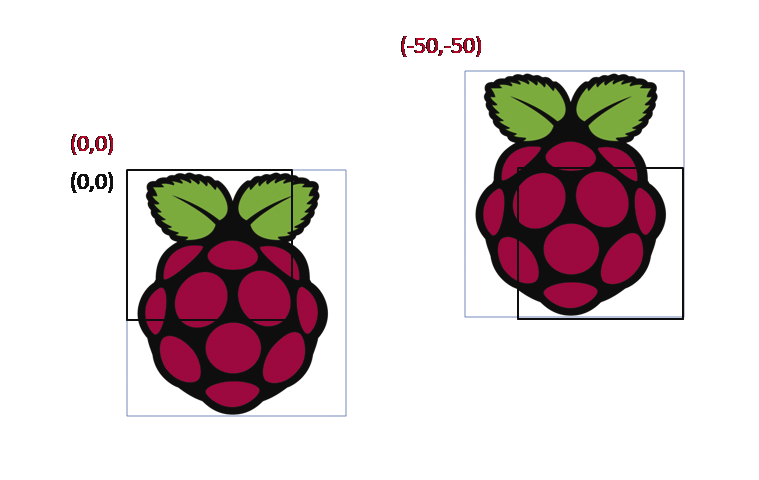

The implementation is built on Blinka for the sensor and PyGame for the interface. PyGame is a game engine, but it is also suitable for other applications. Moving objects is understandably as easy as pie (groan) for PyGame. Instead of moving sprites, the software shifts the image to show a different section each time (Figure 3).

In PyGame, rectangles stand in for both the screen window and the image. The window defines the global coordinate system, and its upper left corner marks the zero point; the (0,0) coordinate in turn determines the location relative to the screen. If the coordinates are (0,0), users will see the upper left part of the image (Figure 3, left).

If, on the other hand, the coordinates are negative, say (-50,-50), the top left corner is outside the window, and you see the bottom right area of the image (Figure 3, right). This arrangement might sound confusing at first, but moving the image toward the upper left (negative coordinates) makes the bottom right part of the image visible.

PyGame is controlled by events. The program processes key events for the four cursor keys (Listing 1, lines 12-17). Each key is backed up by a method that is responsible for moving in one of the four directions. To keep the code manageable, a key-value pair is defined up front for each direction (lines 2-8).

Listing 1: Keyboard Control

01 ...

02 self._MAP = {

03 K_RIGHT: self._right,

04 K_LEFT: self._left,

05 K_UP: self._up,

06 K_DOWN: self._down,

07 K_ESCAPE: self._close

08 }

09 ...

10

11 ...

12 for event in pygame.event.get():

13 if event.type == QUIT:

14 self._close()

15 elif event.type == KEYDOWN:

16 if event.key in self._MAP:

17 self._MAP[event.key]()

18 ...

Processing Gestures

Gesture processing is handled in a second thread that polls the sensor (Listing 2, line 4) and, from the detected gestures, simply synthesizes the matching key events for the PyGame main program (line 16), which closes the circle.

Listing 2: Gesture Control

01 evnt = {}

02 while not self._stop.is_set():

03 time.sleep(0.1)

04 gesture = self._apds.gesture()

05 if not gesture:

06 continue

07 elif gesture == 0x01:

08 evnt['key'] = pygame.K_UP

09 elif gesture == 0x02:

10 evnt['key'] = pygame.K_DOWN

11 elif gesture == 0x03:

12 evnt['key'] = pygame.K_LEFT

13 elif gesture == 0x04:

14 evnt['key'] = pygame.K_RIGHT

15

16 event = pygame.event.Event(pygame.KEYDOWN,evnt)

17 pygame.event.post(event)The program shown here with the gesture control does not completely solve the problem. You still need to convert your printed recipe into a (JPG) image, but you can easily scan or take a photo of a recipe book or grab a screenshot to do that. Fairly low resolutions are absolutely fine for the purposes of this application.

If the recipe is a PDF, the following one-liner will help:

convert -density 150 in.pdf -append out.jpgThis command uses the convert command from the ImageMagick package, which is typically already in place. If not, just grab it with your distribution’s package manager. The -density option lets you control the image resolution. If the PDF has multiple pages, the command arranges the pages one below the other. If you prefer horizontal scrolling, replace -append with +append. Two more parameters handle fine tuning: -trim removes the white border, whereas -sharpen 0x1.0 sharpens the result.

You still need two things before you can start the image viewer with a double-click: a pi-image-viewer.desktop file, which registers the image viewer as a program for processing JPGs, and a file that stores the image viewer as the default display program. Both points are described in the Readme file for the GitHub project.

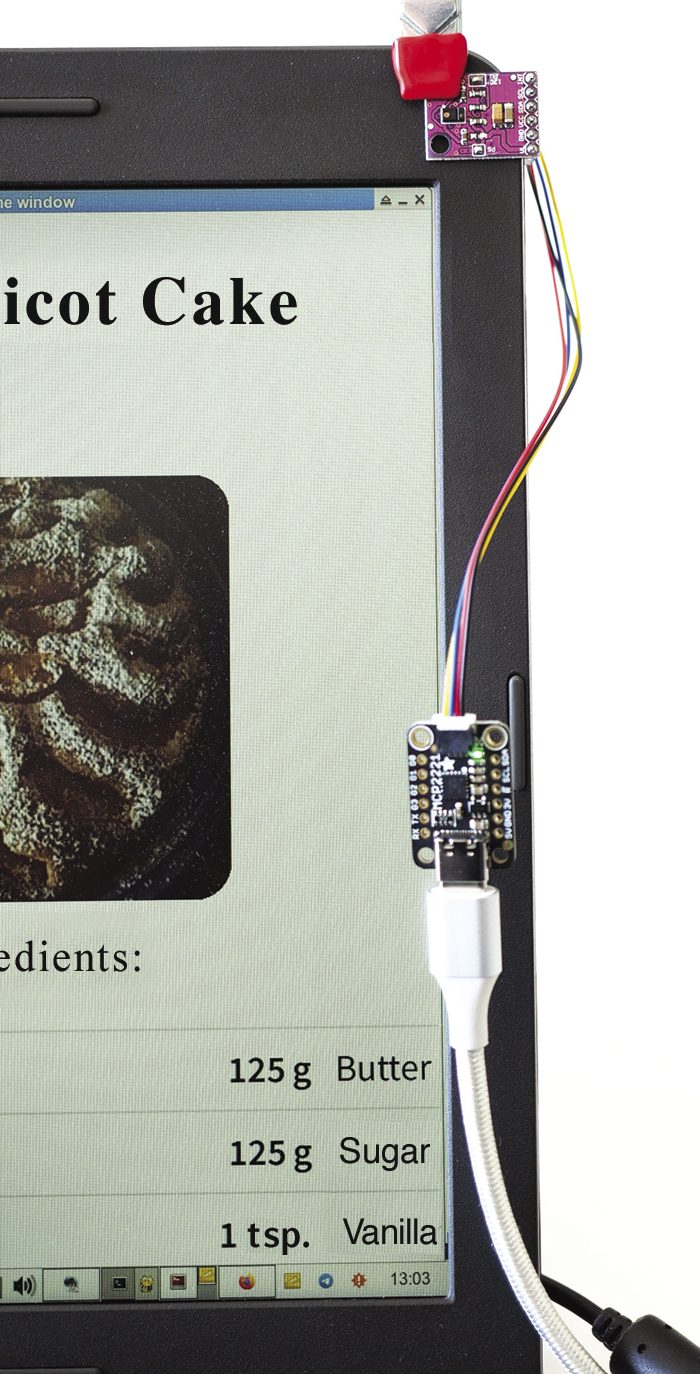

Laptop Instead of Pi

The image viewer and gesture control also work without a Pi on a normal laptop (Figure 4), because Blinka and PyGame run the same way on popular desktop operating systems. However, because these systems don’t usually have a freely accessible I2C port, you might need to retrofit one on a USB-to-I2C bridge. The MCP2221 microchip does this easily and inexpensively for $3.00 and up or with a Raspberry Pi Pico.

Conclusions

A few lines of PyGame code and a few lines of APDS9960 code, mostly copied from sample code online, is all it takes for this application. Because the key events are simulated, you can do without a keyboard. The principle can also be transferred to other hardware. For example, you can find low-cost displays without touch input. Instead of a full keyboard, a simple MPR121 keypad (this keypad is retired) connected by I2C might also do the trick. Just as the code in the image viewer translates gestures into strokes, it would translate touch events for the key sensor.

You can take this solution one step further with the python3-evdev library, which lets you generate arbitrary (system) key events, allowing you to control any program with gestures or by touch – not just those that are designed for touch control like the Pi Image Viewer.

Voice control is an alternative to gesture control and is now suitable for practical use on a Raspberry Pi with voice interface modules such as the Seeed ReSpeaker.